My Journey into Econ PhD

In Oct 2020, I wrote a series of article on ‘how to break into tech’ from an econ phd perspective. The enormous attention the series got made me realize this sort of public good may be under provided. Thus, I decided to fill in the back-stories as well: how to ‘break into’ the Econ PhD.

In Jan 2014, I came to study at Harvard University as a ‘Visiting Undergraduate Student’ (VUS) for a semester. At that time I just finished the first half of my junior year at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) in Economics and Finance. Little did I know, two months later, I would have reneged my Investment Banking summer internship offer in HK, and embark on a new journey— research in Economics.

Why exchange at Harvard?

Coming to HK to study ‘business’ wasn’t what I dreamed of when I was 18— I had wanted to go to Peking U to study history or sociology, because I have always wondered how the world came to be the way it is + why society works the way it does. But (1) my dad laughed it off and demanded that I study something useful and (2) I was 7 points short from the admission cut-off for PKU in the National College Entrance Exam (高考).

HKUST is one of the best institutions in Asia, but it wasn’t my cup of tea — I had always thought that ‘college’ is a place where you dive deep into knowledge, talk about dreams and passions and ideas with a group of friends. Instead, what I was encountered by was an extremely business-oriented environment: most people were there to get the degree so as to get a higher paying job, and everyone is slacking in classes so they can use the time to do internships, and the professors know that and it’s reflected in the teaching.

Very disappointed, I thought about transferring to US undergrad. But just as I was preparing for SAT and such, I got to know ‘China Entrepreneur Network’ (CEN), a global organization whose mission is to solve social problems using ‘social entrepreneurship’, i.e. ‘firms who, instead of maximizing profit, maximize social impact’, and CEN was trying to establish a HKUST Chapter. Super excited about the idea, I spent the next 2.5 years building CEN’s HKUST Chapter and in the social entrepreneurship space in HK and Mainland China, but the more time I spent, the more disappointed I was: in fact, most people in this space were ‘scammers’ who were using ‘social entrepreneurship’ as disguise to get funding, etc. for their personal benefit.

However, because of my achievement in the social entrepreneurship space in HK, I was invited to participate in Stanford VIA’s summer program right after my sophomore year. It blew my mind — I learnt ‘design thinking’ for the first time, got to know a start-up who help ex-prisoners get back to a normal life, talked to a bunch of leaders in the social innovation space around the world. It was *so* different from anything I saw in the ‘social entrepreneurship’ space in HK. I realized — I have to spend some time in the US.

How to exchange at Harvard?

The normal route would be to use HKUST’s exchange program, but it’s too competitive: the whole business school, which has probably 1000 students per cohort, have 2 spots for NYU, and that’s already the best institution partner HKUST B-school has, and every year it’s some ‘Global Business’ (GBUS) student getting it (GBUS is HKUST b-school’s ‘flagship program’, which is not what I was in). In fact, this situation is broadly true for universities in Asia: it’s very hard to get a very good undergrad exchange via the university, because resource is extremely scarce.

So why don’t I apply by myself? Almost all US universities have its own ‘Visiting Undergrad Student’ program: Harvard has it, Yale has it, Columbia has it… Stanford doesn’t have one during academic quarters but has a summer school. For these programs, *anyone* who is an undergrad anywhere in the world can apply.

It’s all about your rec letters and your essay. With my achievement in the social entrepreneurship space + my genuine passion for social sciences, it wasn’t hard for me — I asked Joshua Derman, a humanities prof at HKUST who holds a PhD from Princeton and BA from Harvard, and Po Chi Wu, a then-HKUST adjunct prof / CEN faculty advisor / long-time Silicon Valley VC for letters.

I took Prof. Derman’s class on ‘Dictatorship: Stalin, Hitler and Mussolini’ and did very well — it’s one of the few classes I took from HKUST where the sparks of knowledge fly — both Prof. Derman and I were genuinely interested in understanding the history/how human society worked, which is rare in a super business-oriented HK. When I took the class, I wasn’t aware that I was going to ask for a letter. Genuine interests in things go a long way.

The first half of my junior year was a turning point for my undergrad — I was applying for investment banking internships and US visiting undergrad programs at the same time, and did well in both: I got offers from JPMorgan and Merrill Lynch, and Harvard and Columbia. That’s it: I’ll spend the second half of my junior year at Harvard, indulge myself in knowledge, and come back to HK to do my investment banking summer internship, get a return offer, and spend my senior year chilling.

Why Econ PhD?

But it never came true — 2 weeks into my exchange at Harvard, I changed my mind.

First, it’s because my long depressed thirst for ‘knowledge’ bursted out — imagine a person addicted to chocolate, was placed in an environment with no chocolate for 3 years, and suddenly was dropped into a warehouse of chocolate — that’s me. I took James Robinson’s economic history class, and was in heaven — these are exactly the types of questions I’ve wanted to understand since I was 15, and after a *long* delay I finally got to get it.

Second, it’s because incidentally, YG, my middle school classmate, was also on the Harvard VUS program that semester, and he was applying for a Econ PhD. I’ve never given it a thought before — when my dad asked me ‘what’s your thoughts on becoming a professor?’ when I was 18 my answer was ‘I don’t like teaching the same material over and over again.’ Through YG, I finally got to understand what ‘professorship’/’research’/’PhD’ actually means. — It’s amazing how much information friction there still is, but like it or not, people’s info still mostly come from their immediate network. I stepped into investment banking because I accidentally came to HK and that’s what everyone there is doing and as a result, the career path I have the most info about.

From YG, I realized that I might actually like Econ PhD + a career as a professor a lot: (1) I love thinking about how the world works, and that’s what research is about (2) I get to choose what I work on (3) I can influence policy, thus change the world on a larger scale than social entrepreneurship — I realized none of these is true after I’ve actually spent 5 years of my life in econ research, but at that time, clearly neither YG nor I have a great idea. This is another lesson — don’t listen to the advice of someone who is *trying to break into a field*, the grass is always greener on the other side.

How to Econ PhD?

I again got it the easy way — YG has already figured it out, and he basically told me the ‘playbook’ — work for Raj Chetty as an RA, and you’ll get into Harvard/MIT.

He was an undergrad at Tsinghua — top 2 universities in China. However, to get into top 10 econ phd in the US, that’s not enough, and if anything, maybe a slight negative:

- It’s extremely hard to become top 1/2 in your cohort at Tsinghua, because everyone is *extremely* good

- Even if you’re top one or two, you may still not get in, because US top econ programs may not know how to read foreign undergrad’s transcripts

- Even if they know — because, to be fair, Tsinghua often place people into top US econ grad school — it’s not enough, because any US school applications nowadays, be it undergrad, visiting, or grad school, it’s all about the rec letters.

A good rec letter is a combination of 2 things: (1) the recommender being strong (2) the recommendation being strong. Even if your undergrad prof says you’re gonna win a Nobel Prize, it might not mean anything, if she/he is not ‘in the circle’.

What is ‘in the circle’? That’s the key to understanding the game. In 2020 in China, there’s a word that’s super popular — 内卷. In English terms, it basically means ‘cultish’. Society nowadays, either in the US or more broadly, has become extremely cultish. You need to be ‘in the circle’ to get anything done — in the start-up world it’s YC, in econ research world it’s Harvard/MIT/NBER RAs (research assistants).

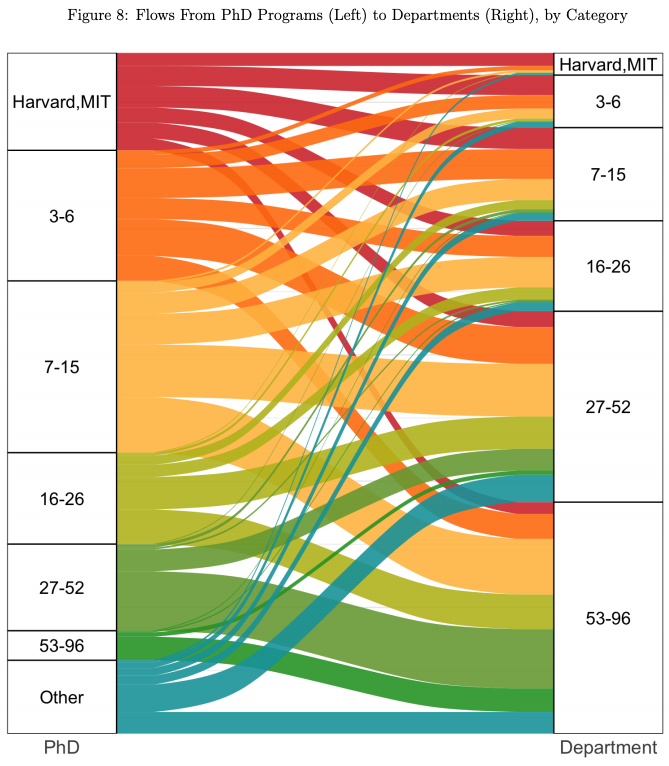

To raise a simple example: 30% of QJE (~top 1/2 econ journal) publications has at least 1 Harvard/MIT faculty in it — that’s insane! And also this:

this is from a paper ‘Staying at the Top: The Ph.D. Origins of

Economics Faculty’ which probably won’t get much attention beyond Twitter because it’s not written by Harvard/MIT faculty, but you should really give it a read: US econ academia nowadays essentially has a ‘caste’ system — where you come from determines where you’ll end up in the ladder. (Isn’t it true more broadly in US society also?)

This isn’t saying ‘you won’t have a good life’ if you don’t follow the ‘playbook’. There are nice discussions about this on Roburt Dur’s and G.C. Pieter’s threads. Here we’re only talking about ***if*** you want to play this game, i.e. top econ phd programs, how to get there:

To get a top US econ phd, e.g. top 20, you’ll need ‘strong letters’, i.e. strong recommender + strong recommendation. The best way to get it is to work as a research assistant for a full year or two at a top institute, e.g. Harvard/MIT/NBER, etc.

Why? Of course you can get letters by taking classes and acing them, but being good at classes is very different from being good at research. There are of course people who can get A+ from all grad level first year classes, but it’s hard, and even if so, it might still be not enough these days, because it doesn’t speak to your research potential.

Why is working as a part-time RA during my undergrad years for a prof. at my undergrad institute not enough? Well it could be — there are people who didn’t work as an RA full-time who got in top programs. But nowadays, the bars are rising rapidly: there are people who has straight As from undergrad, and did a master, and worked as RAs full-time, who has strong letters from their RA bosses who are well plugged into top econ academia. Why would the admissions committee choose you who is a fresh undergrad over them who has proven track record?

Of course, there are other ways to get there:

- If you are a IMO gold medalist, you can ignore the above, because your extreme math ability is enough to convince the admission committee

- Some top European masters program consistently place their top students into top US econ grad schools, e.g. LSE, PSE, TSE, etc. There are some in the US too: Duke has a research-oriented master program in econ. But you basically need to be top 1 or 2 in those to directly place into, say, Harvard/MIT

- If you’re a Harvard/MIT undergrad who has started working as a research assistant part-time for the faculty since, say, your sophomore year, and you did well, and took grad classes and Real Analysis, and got As, you can also ignore the above

In other words, you either need an extremely strong and not-noisy signal about your math ability, like the IMO gold medal, or, someone in the system to vouch for you. — There’s objective standard for math ability, but on research ability? It’s all subjective, and as a result, from whom the opinion comes from becomes the key.

How to check if they are ‘in the system’? Check their past placement record. For example, HKUST consistently place their undergrads into BU and Rutgers’ econ phd program, because there’s an already-established relationship. Once there has been one or two initial cohort that did well, the US econ program knows the quality of that foreign institutions’ undergrad students, and also knows how to read their letters, which help future cohorts.

How to know if that person in the system will write a strong rec for you? This is trickier. Some professors will refuse to write a rec for you if they don’t think they can write a strong rec, which is great, because otherwise they waste your time, and it’s not good for their track record either.

But there are some who wouldn’t say that, and/or they don’t know how things work. There’s anecdotes where a UK prof writes a letter that describes a student as ‘quite good’ — quite good in English English means ‘very very good!’ but in the US econ academia rec letter language it means ‘bad’. — right! There’s a certain way to write letters, which ‘everyone in the circle’ knows, and if the letter isn’t written that way, sometimes it’s simply tossed away.

Again, checking that person’s track record of placement helps — if she/he has never placed anyone into top 20, it’ll be very unlikely you’ll be the first. — again, it’s not about your ability, it’s about their distributional network. And just ask: ‘Do you think I should apply to programs outside of the top 20?’ And that should be a natural starter of an honest conversation on where they think they can realistically place you into, which shows you how strong they are planning to write the letter.

How to Econ RA?

Now that I know I need a full-time RA job with one of the faculty here at Harvard (or MIT, or NBER), the question is how to get there.

I remembered how I ‘broke into investment banking’: to get a full-time job, you need a summer internship; to get a summer internship, the best signal is already having done a semester part-time internship. This ‘playbook’ is probably true for other fields as well.

When in doubt, just ask — this is another good lesson that applies widely. Aggressively use your personal/social capital. You can always pay it back later. So I again asked my had-everything-figured-out friend YG, ‘so how to get a part-time RAship?’ His answer was surprisingly simple: just go on Harvard’s econ department’s website, and there’s a channel where faculty posts RA job postings.

I was skeptical: but why would they choose me over an ‘actual’ Harvard undergrad?

YG’s answer surprised me again: you think all Harvard undergrads want to go do an econ phd? Harvard undergrads have too good resources and as a result way too many distractions: they can spend time in fraternities/sororities, work on a start-up, look for investment banking jobs… and most of them are trying to do all of them at the same time. You think they would care to work hard on a part-time RAship that will bore them out of their mind?

If you haven’t realized yet, part-time RAship for undergrads are usually ‘dumb work’, e.g. ‘manually check for errors in this fuzzy merge’, ‘translate this dataset from Chinese to English’, ‘click through this website to download the data’ — there is always a dirty part in an empirical research project, and someone has to do it, and it’s always the undergrad.

What’s more, there’s sometimes work that only me as a foreign student can do — I went on Harvard econ’s website, and found that there is an RA posting particularly looking for Chinese speakers — Prof MA works on economic history, and was starting a project on the economic history of Taiwan.

I applied, and went to her office for a chat. Of course I was extremely nervous, and was planning to talk about my love for economic history dating back to my high school years. To my surprise, it wasn’t an interview at all — MA explained to me the background of the project (which I didn’t understand much because my English was still bad at that time) and told me what the work was —figure out what datasets are on this website, and translate it from traditional Japanese/Chinese to English.

Simple task, right? But to me that’s the only wood board I had in this giant ocean, which, if I lose, I have no idea when the next will be — I have to do it well.

I immediately started working on it — I went to the website that holds the data, clicked through all buttons through all layers to figure out the overall ‘structure’. Created an excel where each tab was a different dataset, with a cover page describing the relationship and back-info of each dataset (e.g. who collected it, why was it collected, was it a one-off or a regular thing, etc.) Under each tab, I had the year/time period the data was collected, what’s a unit of observation, and of course, translation of each variable, and a more detailed description of what the variables meant, and their relationship.

After sending the excel over, MA very quickly replied with a super long email — I did it! She was happy with what I did, replied asking more detailed questions, and assigned me new tasks.

I kept on working, and started to get introduced to more and more team members on the project, and even started to help onboard new RAs. YG was right — most of the RAs were not Harvard undergrads: they were almost all Visiting Undergrad Students, or master students.

And before I realized, it’s already been more than two months that I had worked for her. One day, she called me into her office, which I thought was a goodbye. To my surprise, she asked if I wanted to work for her full-time for the summer — wow! I made it! So I sent an email to Merrill Lynch to renege my offer, which, they never replied to, understandably.

The summer job was more demanding — instead of working alone, I now have to manage a team — I’m of course flattered, but also scared — who am I to manage a team for a faculty at Harvard? Well, the fact that she assigned me the job means she believes I can do it. So who am I to argue with a Harvard faculty on this?

The summer went well — I further fine tuned my ‘procedure’ for systematizing new historical dataset, and taught it to the new summer RAs, and we now are onto the second stage — using OCR or data entry to digitize those historical datasets.

What classes to take?

At the same time, I also extended my visiting at Harvard from 1 semester to 1 year, so I can keep working for her, and take some grad level classes and Real Analysis to strengthen my profile. During my year at Harvard, I took and got A’s from 6 courses: an undergrad economic history class from James Robinson, an undergrad level econometrics, a master level class at Harvard Kennedy School ‘Designing Government Policy’, Real Analysis, a 2nd year grad level class at MIT on Development Economics, and Senior Thesis Seminar, so that I can write a paper.

The undergrad economic history and the master level ‘Designing Government Policy’ were things I wanted to take myself but weren’t that useful for grad school application, because there is essentially no signal value. — Because of grade inflation, A’s from undergrad/masters class don’t mean anything, and the class also was too easy to get a strong enough letter from.

Undergrad econometrics was a ‘bare minimum’ —I hadn’t had any econometrics before that in my undergrad. When I finally went back to HKUST after my visiting at Harvard, I took the 1st year grad Econometrics at HKUST, which was recommended by MA because she said ‘econometrics is actually useful for research and you should know it as early as possible’.

A in undergrad level Real Analysis was a ‘must’, plus a full score in the math section of the GRE (which I didn’t get). — in fact, a ‘must’ is an over-statement, because there has been people with C in Real Analysis getting into Harvard econ phd because his letter was *extremely strong*. The point is, having A in undergrad Real Analysis is so common nowadays that not having it is a minus.

The Senior Thesis Seminar was such that I can work on a piece of independent research under MA’s supervision, so that in her letter she can credibly talk about my research potential. The 2nd year grad level Development Economics was such that I can get other rec letters from faculty at Harvard/MIT, i.e. in the circle.

For those of you who don’t know: 2nd year grad classes aren’t harder than 1st year, in fact, they are easier, because they are ‘field classes’. 1st year grad classes are pretty much standard across econ phd programs, and are ‘mathy’, which can serve as a screening device: an A in 1st year grad micro at Harvard or MIT is a very strong signal that you’re above the bar. This will be especially true at places where they still use 1st year class grades to screen out some of the incoming PhD cohort. However, 2nd year classes are different at different places, and the faculty has a lot of discretion over how to grade. And since there is no screening purpose, sometimes everyone gets an A, and as a result there isn’t as much signal value as 1st year classes.

You can see that the course taking was very much ‘calculated’, and was communicated between me and MA — that’s the best scenario. Your main letter writer, i.e. RA boss, has the responsibility to ‘sell’, i.e. distribute you. As a result, it’ll be best if they also have discretion over how you shape your profile. For example, the reason why I did not take any 1st year grad class at Harvard was that, *if* I get, say, a C, then it will be very hard for her to sell me. But even if I do not have an A from grad first year micro at Harvard, she can still sell me with her letter. So why would I do something with limited upside and a lot of downside?

There were mistakes — at one point I was talking to different Harvard econ phd students asking them how they applied and what were their recommendation. One person said ‘You need to get a letter from someone who has a lot of influence, for example, if you can get a strong rec from Larry Katz you’ll get into Harvard’ which led me to audit Larry’s 2nd year class (which I later stopped going because I was overloaded). Another person said ‘All they care about is your math ability. I got straight A’s from all the math classes I took and had my math professors wrote me letters’.

In hindsight, these are all wrong — not because the content was wrong, but because it didn’t come from my main letter writer / RA boss MA. Grad school application, just like any other application, is a full package. You need a consistent story. More importantly, just like placement, you need to identify with a group. For example, the math person got in Harvard probably because he was recognized as a theorist. The person who got a letter from Larry was probably recognized as a labor person. Me, instead, because of my RA work and course work, will be recognized as a development/history person, and if I want to ‘place well’, my other parts of the package should speak to that story too, for example, more letter writers in this field.

And that’s what I did wrong — instead of having all three letters come from the same field, I asked JY, the prof who taught the HKS master class ‘designing government policy’ for a third letter. That didn’t work very well: first, he is ‘public’, i.e. not development/history, which made my profile look inconsistent; second, even though I got an A, I didn’t talk enough in the class to leave a super strong impression; third, and most importantly, I mentioned to him that I’m interested in policy after my grad school, which is a big no-no — the only acceptable answer to ‘what do you want to do after grad school’ is ‘I want to be a professor at a top school’. Why? Just think from the department’s perspective: the PhD program is very costly — they fund the students for 5 years and most of them do nothing. The only ‘return’ to the department is good academic placement, i.e. assistant professors at top econ departments, which is a part of an econ dept’s ranking. If you weren’t planning to go into academia in the first place, there’s no point a department wasting resource on you. Yes — yet another sad truth about top econ academia nowadays.

Application

During my second semester as a Visiting Undergrad Student at Harvard, MA asked me if I want to work for her as a full-time RA for a year, which I of course said yes to. 3 months into my full-time RAship, in Sept, she asked me if I want to extend my RAship to 2 years.

The correct answer really should be ‘yes of course’ — If I want to *maximize* my application outcome, 2 years is always better than 1 year. And most importantly, my 1st year was spent mostly on collecting and cleaning data, and MA said if I stay for another year, I can start coauthoring with her on the paper, where I get to do actual analysis.

But it was a hard one for me. First, as the worker, I have private information the boss doesn’t know — I don’t think the data cleaning will be done in 1 year’s time. Second, I was already *really* bored of my job by that time, and can’t wait to be done (understandably — I’ve been managing teams and doing manual data cleaning, instead of analysis, up until that point). Third, and most importantly, I don’t want to do economic history/development anymore. I thought I loved economic history — remember my excitement taking James Robinson’s class — but what I didn’t realize is that consumption and production of research are very different. What I liked is consuming economic history research: listening to and thinking about interesting theories of how the world come to be the way it is, but not actually spending years collecting data and work on very specific and very micro questions.

So I said no to the invitation, and started applying for grad school:

- GRE: I spent non-trivial amount of time prepping for the Verbal and Writing, and took the test multiple times to get the Verbal above 160, which in hindsight was a waste of time. As MA said, no one cares about the GRE as long as you have a 170 on the math section — which I didn’t even get… which didn’t stop me from getting into Stanford

- Statement of Purpose: I again spent time revising it multiple times + asking for help from then-Harvard econ phd students, which again turned out to be a waste — ‘nobody reads SoPs’ says more than 1 faculty in econ. Usually they only read your SoP *after* you got in to figure out which field you are and which faculty they should assign to send emails to you to convince you to come. Also, you should make sure your SoP is aligned with the letters — for example, I said I wanted to do economic history / development, because MA is in this field and she is my main letter writer and my RA work was in this field. You should send your SoP to all your letter writers for feedback — this is a chance for you and them to get on the same page and align your stories. You might say, ‘but didn’t you already decide to not do economic history / development?’ — you can always switch field after you get into grad school, which means in the application, you should focus on how to get into the best program you can get into, and once you’re in, worry about picking fields/professors to work with

- Letters: Of course there’s the letter from MA. I also asked for a letter from SA, a Northwestern faculty who was visiting MIT at that time, when I took the 2nd year grad Development. Why did I not ask for a letter from BN, the MIT faculty who co-taught the class? It’s a huge mistake. At that time, I thought I can only ask for 1 letter from faculty teaching the devo class, because otherwise their content will be overlapping. In fact, it’s totally wrong —First, they taught different parts(!) so the content will be different. Second, they have *different connections* — the MIT dept will of course take more seriously an MIT faculty’s words than a visiting faculty, and vice versa for Northwestern. Again — grad school application is fundamentally about the letter writers’ distribution network. Different people have different distribution networks, so even if two people taught the same class, it’s still ok to ask for letter from each of them!

- Coursework/Transcript: I had A from Real Analysis, which is pretty much the only thing that mattered. If you’re from a US undergrad who often place people into top econ phd, your undergrad transcript will matter because they know how to read it. In my case, HKUST is a place that just doesn’t place students into top US econ phd programs that much, so as a result, my transcript from HKUST actually didn’t matter at all — it worked well for me, because my grades weren’t good at all (3.7 out of 4.3). Instead, because I spent a year visiting Harvard, all that mattered was my Harvard transcript. But, most of the classes I took had no signal value at all, as I said before. So the A in Real Analysis was essentially the only piece of info that’s useful on my transcript. (I was dumb enough to take a probability class during my last semester at HKUST because I thought I didn’t have enough math — the truth is, as long as you have an A in Real Analysis from Harvard, it doesn’t matter anymore if you didn’t have math classes easier than that. Of course having A’s in harder / grad level math or stats classes is a plus but it’s unnecessary given my strategy, i.e. being sold as an empiricist instead of theorist.

The strategy should always be ‘apply everywhere’, because once you have the application packet, the marginal cost of applying to one more place is almost zero. This is not technically true because of the application fee, but for people in financial hardship, you can and should apply to waive the fee, in case you didn’t already know. I eventually applied to around 20 places: Harvard and HKS, MIT, Stanford, Berkeley, Northwestern, Yale, Wharton, Columbia, NYU, UMichigan, UCLA, Brown, Duek, UCSD, Cornell, BU, BC, LSE, and got in 5: Stanford, Northwestern, Wharton, UMichigan, Cornell.

When I got rejections from Harvard, MIT, HKS, Yale, etc. I realized something went wrong. At that time, I was working at NBER — National Bureau of Economic Research, hanging out with a group of NBER RAs, who mostly work for some super big shots like Raj Chetty, Amy Finkelstein, David Laibson, etc. and all of them (maybe except 1 + me) in my year got basically either Harvard or MIT or both.

I was confused — I had thought that I played it right — followed all the steps in the ‘playbook’, did a full-time RA, took real analysis and got A. What did I miss?

When something like this happens, the person tend to over-think a lot — I thought it might be because MA didn’t like me that much after all. Turns out I was wrong — the fact that I was able to get into Stanford means she must have written a strong rec for me. In fact, I’m pretty sure she called her friends who are faculty at Stanford to tell them they should admit me. — after not getting into Harvard and MIT, I went to her to tell her the situation and asking her what to do. Very soon afterwards, I received Stanford’s offer. And later when I went to the campus visit day, I realized it’s RN in charge of admission that year, who is a big shot in economic history, i.e. same field as MA.

You might think the ‘calling her friend up at X university’ is an exaggeration, but it really isn’t. Either at the level of placement or admission, people strongly rely on network / word of mouth. Among the hundreds or thousands of apps, why would they look at yours? It will be a much stronger reason if someone they know at another university called them to say ‘hey you should take a look at this kid’s profile; she/he is very good’.

In the series I wrote about finding a tech industry job, I more than once emphasized the importance of referrals. This is true essentially in any field anywhere nowadays. Of course it will be hard for you to ask your professor if he/she can make a phone call for you. But for example in my case, constantly updating the prof. how you did in your application, and if they want to and can, will do what they can to help you in this or next cycle, i.e. call their friends.

How to do well in Econ PhD

There are lots of articles on ‘how to present’ or ‘how to structure a paper’ for job market candidates, but there seem to be fewer articles in general on ‘how to do well in grad school’.

The problem is, for those who did well + went into econ academia, this is a topic too sensitive for them to write about. For those like me who decided to leave econ academia, even if I write about it, no one will listen because it’s not credible.

Let me just say the following are things I heard from people who actually did well but don’t want to write it down and publish it themselves:

First, you should figure out what you care about. Are you here because you want success? Or because you want to work on the things you want to work on? These two are very different, and will mean different strategies for your grad school. The rest of the article is based on the assumption that you want to climb the status / success ladder in econ academia. If not, you can ignore it.

Second, you need to realize econ academia is fundamentally cultish in nature, and there’s little you can do about it. For example, ‘IO’ (Industrial Organization) is essentially defined by AP; ‘Development’ is basically defined by the ED/AB experiment crowd, etc. To do well, you need to be recognized by one of the cults as ‘one of them’.

You might think this is crazy, but if you think carefully about it, you’ll realize this is just a distillation of human society. In high school, almost everyone is part of a ‘group’ — you hang out together, you support each other. There’s of course always people who are ‘weirdos’ who are not part of any ‘group’. But as a result, they are often the target of bullying — because the cost of bullying them is low (because if you bully someone who is part of a ‘group’, you’re essentially starting a fight against a whole group, which is much harder to handle than a fight against an individual). As the ‘loner’, you have no one to talk to, no one to hang out with, and no one to support you.

Into music / modern art, there are also always ‘groups’: classical, impressionism, realism, etc. How to judge if a song or a drawing is good or bad? In something this subjective, there’s no such thing as ‘good vs bad’, it’s all opinions. As a result, it’s never about being ‘objectively’ good, but more about creating art in a style that talks to a specific audience that wants to see this form of art being developed, i.e. a cult.

Econ is the same — although econ wants to believe it’s ‘science’, it’s not — Should we set tax at 45% or 75%? Is free trade good or bad? It’s all opinions, because there’s no objective truth when it comes to human behavior or human interactions — it all depends on the context. As a result, you can always find cases to support point X, and cases to support the opposite of point X. The good thing about it is that, more people can publish papers because literally anything *can* be written. The bad thing is, it’s not about being objectively ‘good’, but about how to ‘sell’.

As soon as there are more than 3 people in a room, people start to form coalitions. Friends and enemies start to emerge. You as an individual, will need to pick a side — yes, not so different from what you were doing in high school, or what countries were doing in WWII — human nature doesn’t change that much, does it? In order to ‘publish’, you don’t need to please everyone, or even be right. What you need is to figure out which cult you’re trying to join and trying to please, and learn their ‘rituals’, be it complicated IO structural models, or cleverly designed IV/RD/experiment.

So now that you’ve understand this, the rest is easy:

- Always go to the strongest department. For example, if you have MIT/Harvard don’t go to Stanford. If you have Stanford don’t go to Northwestern, etc. unless you have a very very good reason, e.g. you’ve already started coauthoring with a big shot at the school who clearly will place you well when you’re on the market

- Once you get into your program, figure out which professors place well / which field is the department strongest at. For example, if you ended up at Stanford, please don’t do econometrics (unless you go across the street to the business school to join SA/GI’s causal inference /machine learning crowd). I once heard the students complaining in a Town Hall meeting ‘why isn’t there an econometrics seminar? why isn’t there more econometrics faculty?’ and was thinking ‘if you had wanted to do econometrics why would you have come to Stanford?’

- Professors who publish well and professors who place well are not the same! The biggest common mistake 1st years make is ‘oh I want to work with RC’ —have you heard of anyone who’s main advisor is him and placed well? He has a group of full-time RAs who churn papers out for him; he doesn’t work with grad students. Again, at the professor level, it’s another game: some keep their influence at the department by placing students well, some do so by lots of QJE/ARE, and some decided to not play this game anymore and do consulting all day on the side. You really should figure out who is doing what — who is important in the department; whose strategy was writing lots of papers, and who has a track record of always placing students well.

- Of course on the job market there’s a ranking: every department ranks its job market candidate into several tiers: push as stars (at places like Stanford, maybe 1/2 each year, but MIT/Harvard can have a lot more) i.e. top 5, top 10–20, top 20–50, not good for academia. Of course it’s easy to get into a competitive mindset, but the best thing you can do is to (1) pick a good advisor who will and can vouch for her/his student because she/he has always placed well and have the credibility to say someone is good (2) write the best job market paper you can so that they can credibly say you’re good. Sometimes the strongest advisor’s 3rd best student place better than a median advisor’s best student — for example, in 2016, DF’s 3rd best student placed into UPenn. That’s already an extremely good placement by Stanford’s standard — yes, the gap between MIT/Harvard and even Stanford is huge. MIT can consistently place almost all of its students into good academic placements, while maybe half of Harvard can, whereas maybe 1/5 of Stanford can

- But after all, it’s really on you having a good job market paper, and good presentation. If you don’t have a good JMP, no amount of ‘following the playbook’ will help you. Also, once you get the interview, the rest is on you: no matter how strong your rec is, if you did really badly in the interview, you still won’t get a flyout. (Although there are cases where someone failed all his interviews/flyout and miraculously got a job because his advisor made a call, but it’s very rare.)

- So how to write a good JMP? Unfortunately, it’s not ‘writing whatever you want to write the most’ — there’s pretty much a certain way a good JMP should look like nowadays — read recent JMC’s JMP to get a sense. If you’ve picked a good advisor, then listen to their advice — again, similar to my interactions with MA when I was applying for grad school, I pretty much followed all her advice when deciding what classes to take, etc. because it’s her job to sell me and she should have control over how my packet look like. — If I had insisted writing in my SoP that my real dream is to become a theorist, then her letter would be void, because as a good empiricist, there’s no way she can credibly talk about my research potential as a theorist.

- Should you listen to *all* your advisor’s advice? Not necessarily. Advisors appreciate people who can think independently, and convince them that they are wrong. It’s really an art without a ‘right answer’ — there are cases where a JMC later said ‘when I’m on the market everyone asked me that question which my advisor has told me to fix that I ignored’, but there are also JMC who said ‘my advisor thought the idea was shit, but after cleaning it up and presenting it in a better way, they were finally convinced that it’s a good idea, and it eventually turned out to be a good paper’.

- In general, it’s good to have *ideas* that are come up independently and novel — I’ve heard many times that ‘if you work on an idea clearly derivative of your advisor’s work, it’s a very negative signal on the job market’ or ‘AS placed well precisely because the topic of her JMP has nothing to do with her advisor’s work’, etc. But on the execution, you should listen carefully to the advisor’s (conditional on you having an advisor who has a track record of placing people well in recent years) because they know what the market is looking for in a JMP in *your field*: as I mentioned before, there are impressionism, realism, etc. in art and you need to draw in a certain way to be recognized as part of the gang — same for academia. There’s a certain way to write a paper to indicate that ‘you’re an IO person’, or ‘you’re a development person’, etc.

Not hard, right? Just get into a top econ program, choose a field that the department is strong in, and become the student of an advisor who has a track record of placing well, come up with a good JMP idea, and execute well — write it in a way that fits into a certain field’s agenda.

Of course, I’m joking — it’s hard; and there are also of course exceptions — there are people who placed well because they innovated, MA herself included. But on the whole, on average, for the vast majority of people who placed well, they had the field politics figured out, and did what’s consistent with the above. If you strongly believe that you are the type who can do well despite the ‘playbook’, you should definitely feel free to ignore the above, because any ‘guidebook’ by nature is not meant for rare geniuses.

You might be very sad at this point that econ grad school is not a place for you to ‘embrace and indulge in knowledge’, ‘figure out how society works’, ‘work on interesting questions’, but in fact, that’s pretty much all upper-middle class US society nowadays: doctors, lawyers, bankers, engineers, professors. For anyone who want to be a ‘upper middle class’, you pretty much have to ‘follow a certain playbook’ — recall what I did when looking for a tech job, it really isn’t that much different.

It’s part of the reason why I decided to give start-up a try: as far as I can tell, it’s one of the few places where you can do ‘whatever you want’ as long as you make something that there are some people (i.e. users) who find it useful / are willing to pay money for, i.e. slightly less ‘politics’. I can of course be wrong — check back at my Medium in a few years, and I might have another article telling you why you shouldn’t do start-ups :)

Till next time.

Q&A + Miscellaneous

Q: Wait, so did you work for Raj Chetty?

A: No — when working as a full-time RA at Harvard I was funded by the LEAP Pre-Doctoral Fellowship, which is something Raj created, but I worked for MA, not Raj Chetty.

Q: I heard these RA programs only hire US citizens

A: Not true — nowadays many of these programs provide J1/H1B sponsorship. I worked under J1 visa. One important thing you should know is that, if you used a J1 visa, you’re very likely under a ‘two year residency requirement’, meaning that you need to stay at your home country for 2 years (cumulatively) before you can apply for H1B or green card in the US, unless you apply for a ‘J1 Waiver’ from the Department of State + USCIS. If you’re in the same situation, check DoS and USCIS website and your home country’s relevant website for detail.

Q: I’m a master student outside of the US but really want to go to a top US econ PhD. Is it too late? What should I do?

A: As mentioned before, rec letters from ‘within the circle’ is key. ‘within the circle’ doesn’t really mean ‘within the country’ — for example, there are European (or even Asian) universities with faculty who are very connected with top US academia.

For example, LSE’s ‘economics and econometrics’ master program consistently place their top students into US top econ programs; NY Fed consistently places its RAs into top econ programs; Stanford consistently has students coming out from Australia’s top undergrad program; there are often theorists coming straight out of Japan’s top undergrad or master program. Again, to figure out whether your institute / advisor is ‘in the system’, check their past placement records. If you want to figure out which programs are ‘in the system’, check or email them to ask for their past placements, etc.

One good thing about econ academia is that, being ‘old’ isn’t really punished, to some extent. For example:

- there are people with a previous math or engineering phd (or dropped out of such a phd) and got in top US econ phd

- there are people who went to do banking/trading/hedge fund for a few years and got into top US econ phd

But the above people tend to be those who are already connected, i.e. went to a ‘target undergrad’ (i.e. undergrad that consistently place people into top US econ phd), did well in classes, already had strong connections with faculty through undergrad research. Plus, a math phd is a very strong positive signal.

But there are also people who:

- Did a master in China, then another master in the US, then got in

- Did a master in the US, then 3 years of RA, then got in

- Did 2 years of RA at the Fed, then 2 years of RA at a top econ dept., then got in

In other words, if you *really* want to go to a top US econ dept for a PhD, there are always ways, as long as you’re willing to spend time, for example:

- If you’re an undergrad somewhere outside the US in a non-target school, transfer / do an exchange / apply for a visiting undergrad student program, to come to the US, then work as part-time RA, do well, get a summer full-time, then do well, get a full-time RA job for a year (in this process, you don’t need to stay at the same institution/work for the same advisor; you can use their letter to bootstrap upwards: from a top 50 to a top 20, then to a top 10, then to top 5, then to top 2 institution or RA program)

- If you don’t have the money/time to transfer or do an exchange/visiting year, send cold emails to all top 50 US econ dept’s faculty asking to work for them part-time remotely for free. To successfully get attention, you should already know Stata/R and econometrics, i.e. know how to plot graphs and run regressions — in other words, you need to be useful. You’ll find something — probably not from Harvard/MIT, but it’s a starting point. Then, again, you can bootstrap upwards: if you did well in your part-time RAship, ask to come to the US over the summer to ‘work’ non-paid full-time, then use that letter to get in US top master programs or top RA programs, etc.

- If you’re already a master somewhere, things are not *so* different — the above should apply, i.e. either break into the US by education (i.e. another master in the US) or RAship (cold email to start + bootstrap upwards)

- If you’re already a PhD, you can try transferring / doing visiting semesters or years. There are people in Stanford econ (more than one) who started as a visiting PhD student. But to be fair, not all universities have such connections with Stanford econ. Again, every institution/program’s connection, or every faculty’s connection is different — check with your advisor or your department chair and see what they have

- Yet another way is to apply for a program that’s related to econ but less popular and thus easier to get in (because many people don’t know and didn’t apply). For example, at Harvard, other than econ, there’s HBS’s program and HKS’s program, and there’s also the public health program, if you’re already set on doing health econ. At Stanford, there’s not only econ, but also GSB’s econ, GSB’s OIT, and MS&E (‘management science and engineering’ program) whose PhD works with econ and GSB faculty all the time, and some of them even transferred into Stanford econ. At MIT, there’s not only econ, but the Media Lab, and dept of Urban Planning (I’ve met people who are PhD there and work with Ed Glaeser, for example.)

- This might sound unintuitive but location matters: Disproportionately many Harvard/MIT econ phds eventually place into *geographically* adjacent departments such as BU/BC (Why? Because then they can keep working with people at Harvard!). As a result, if you’re a BU student, it’s very likely that your advisor came out from Harvard, and still work with people ‘in the circle’/at Harvard, and it’s very likely for you to go to Harvard as a visiting PhD for a year (again I know someone like this). I don’t think this piece of info is already priced into the dept ranking. So when choosing programs, consider places like BU that seem not in the top but actually has ‘special connections’ with the top

- Other than geographic adjacency, you should consider field adjacency — finance, marketing, accounting, operations research, information, urban studies, health, law and economics… these are all programs that are related to econ, and consistently see econ phds placing into. Econ is very crowded nowadays — this can be seen from the increasing number of RA programs and RAs — many of them have profiles that really should be going to a PhD program, but they are still doing RAs because there are too many people who want to get in. However, these adjacent fields are a lot less crowded — many people wouldn’t even give it a thought, making it easy to get in; placement is also easier, for example, NB at Stanford keep telling his student to consider the accounting job market, because how much easier it is than econ/finance.

Q: Did you enjoy/like/have a good time at your PhD at Stanford?

A: Yes I did. But that’s not the right question to ask.

The Stanford econ PhD is too chill compared to, say, Harvard/MIT:

- At Harvard/MIT there are a lot more people who are depressed

- But Harvard/MIT placement is also much better than Stanford

At MIT, almost 2/3 of the students each year go to decent academic positions, 1/2 at Harvard, 1/5 at Stanford.

I don’t think it’s the input quality. In especially my year and adjacent cohorts, Stanford hired a bunch of young stars (e.g. Raj Chetty, Matt Gentzkow, Heidi Williams, i.e. collecting Clark Medalists), the student input quality is actually not *that* different from, say Harvard, because young naive students chase after big shots (not realizing that faculty who publish well VS faculty who advise grad students / place well are different, as I mentioned in the main article).

Is it faculty quality? There might be still a difference, but I think there are enough good advisors at Stanford across different fields (e.g. theory, IO, macro at Stanford are all strong). In fact, at Harvard, I often hear people complaining there’s no faculty: xx left for IMF, xx left for UChicago, etc.etc.etc. If anything, Harvard these years had net outflow (which might be part of the reason why they suddenly decided to tenure a few young faculty in the same year or two).

Is it because of how nice the faculty are / how much attention faculty give to students? Stanford faculty is the nicest I’ve seen on earth, especially given how nasty people usually are in econ. I often hear my friends at Harvard complain how hard it is to get faculty attention: one student scheduled a meeting with SM, went to his office, stayed there for 20 min, still didn’t see him, gave up and went to the basketball court, and saw SM there, and SM was like ‘hey I’m SM, what’s your name?’; another person said he went to one of his committee member only to find that that person has completely forgot about being on his committee; another person said he was trying to figure out whether he should go on market this year (it’s already Sept) and his advisor keeps ignoring his email… But I have not heard of anything close to that from Stanford — if your experience is different, please let me know!

Is it because of the department’s administration? In fact the opposite — Stanford econ dept is the most student friendly I’ve seen on earth. The first time I went to the annual ‘Town hall meeting’ where students complain about things with the dept chair, I thought it’s just a show. I was shocked to find out whatever the student asked for were actually fixed very soon afterwards: The students in my cohort asked ‘why can’t we enroll in 10 credits over the summer to hit TGR (terminal graduation registration status) faster just like the sociology dept?’ and in the next cohort, it’s fixed. Even something like ‘our department is not environmentally friendly enough — we should use recycle bins’ is fixed in a month.

So what is it? — the culture is too chill. Maybe it’s the fact that we are in Cali, the weather is good all year round, lots of nice hiking trails and beach, not 6 months of snow like Harvard/MIT. Or maybe it’s because the faculty at Stanford is too nice, never say harsh things or critic your ideas, always very encouraging. Or maybe it’s because there’s too much emphasis on student mental health, basically zero pressure, no matter what you do you won’t be kicked out. It’s probably a combination of these, that, as a result, the median Stanford student on the market just has less papers than her/his Harvard/MIT counterpart.

In fact Stanford faculty is quite fond of coauthoring with students (more so than Harvard probably; maybe not so much as MIT) so it’s also not because faculty here don’t work with students.

Before starting my PhD, I had thought all econ PhDs in top US programs would more or less know each other, because it’s such a small circle. But after I started, I realized it’s very much not the case — not even everyone knows everyone within the same department, sometimes not even the same year.

As a result, most of the time students are comparing within the same department, or even same reading group — ‘oh, xx had 3 papers on the market, I guess it’s ok for me to have only 2 in year 4', not realizing that the Stanford median is already much below the top 2, and as a result, they are using a bad benchmark.

You might say ‘it’s all about the JMP’ — it’s increasingly not the case. In recent years, there’s a trend of productivity being rewarded on the market. Also, the case of ‘a star having nothing but a good JMP getting a great job’ often happens at the very top. If you go lower down, departments increasingly care about productivity — not everyone will place into Harvard/MIT and be a RES tour star, so that realistically should be the right benchmark for most people. Also, for many people, ‘I was trying to write a good JMP and that’s why I had only 1 paper’ is not true. In fact, having previous papers will make it easier for you to form a research agenda + come up a better idea + know how to execute.

It’s a long way to answer the question: if you’re looking for ‘having a good time’, it’s fundamentally incompatible with a great placement, and at some level incompatible with a PhD. I’m not saying mental health is not important — mental health is super important, without which you won’t be able to be productive. The key is to realize if you want to live the ‘party each weekend; go out on a beach; cocktail on the side’ life, you really should re-consider your plan to get a PhD. But if you are *indeed* looking for such a life, Stanford is probably the closest.

In all, you should *really* figure out what you’re trying to achieve, i.e. why are you thinking about getting an Econ PhD?

Q: So what are some good VS bad reasons to get an Econ PhD?

A: great question. Let me start with bad reasons:

- ‘Undergrad econ classes are fun/I like thinking about these interesting questions’: Undergrad econ classes are a complete mis-representation of what econ grad school is like and what econ research is about. In chemistry or physics, the undergrad classes teach you the basic version; in econ they teach you the wrong version. Econ departments are smart — they know that, in order to keep econ faculty employed, and keep the whole econ academia boat afloat, they need more young people entering it, including attracting undergrads into majoring economics. To do that, they make the undergrad classes easy (e.g. IS-LM curves shifting around) and fun. As a result, what undergrad econ teaches has nothing to say about grad school or research, which is most of the time math-y, unintuitive, and disconnected from the real world.

- ‘I’ve been working and felt I haven’t been learning things. I want to learn things by getting a phd’: As I mentioned before, consumption and production of knowledge are two completely different things. In undergrad or a master program, you pay the school money and consume knowledge. In grad school, the department pays you money and you produce knowledge aka papers. When you’re paying, you are a customer, and of course it’s their job to make you happy. But when you’re in grad school, you’re a worker/employee, not so different from who you are right now at the firm. It is your job to make sure you’re learning things. You’ll most likely find the first year grad sequence un-interesting/irrelevant, and 2nd year onwards it’s all up to you to learn what you need to produce research, and you’ll be focused on a very specific topic — if you thought coming to econ grad school means you’ll be able to talk about the stock market, Fed policy, bitcoins, macro trends, trade policy, at a dinner table with your family, you’re completely mis-informed. Econ grad school teaches you nothing about comprehending our economy or economic policies in general. Instead it asks you to dive extremely deep into one tiny little topic that most people at a party won’t be interested in

- ‘I’m really good at school. I don’t like talking to people. So I don’t want to work.’: being good at school doesn’t mean you’re good at research. As I said, your job in undergrad or masters is to take classes and consume knowledge. That’s completely different from grad school where you have to come up with new ideas and execute research projects. Also, increasingly, being able to present is extremely important on the job market. If you ‘can’t talk to people’ that’s a very good reason not to come to econ grad school… There are disciplines where ‘salesmanship’ is less important, like hard sciences or lab sciences, where the ‘facts’ are still more important. Econ is too ‘soft’ to be objective, and it’s all about opinions, the story, whether you can sell it, whether you’re in the network, etc.etc.etc. If you really hate ‘playing’ the politics / schmoozing / networking / talking to people / sell yourself, it might not be a great fit.

What are good reasons? Either you *need* the PhD to do other things (e.g. rise up in a gov org) or know how it works and want to play:

- ‘I’m in the Fed/European Central Bank and to rise up the ladder I need a PhD’: go ahead! But notice that in Europe there are PhDs that you can get part-time, so you don’t need to waste 5–6 full years of your life just to get the degree for you to rise up the ladder

- ‘My whole family is in academia/econ academia. I have a lot of insider info, know how the system works, have connections, know the playbook, can get advice on how to succeed in academia from my dad.’ — despite how sad it is, still, in the US nowadays, many of these ‘upper middle class professions’ rely heavily on info/connections. For example, when I was an undergrad, trying to break into investment banking, I realized that you need a summer internship to get a full-time, and need to already have had previous summer internships to get a summer internships at the ‘Bulge Bracket’ banks in your sophomore year. But where to get the ‘first’ internship? — from your family connections. This is true for econ as well: a large part of doing well is knowing the system and knowing how to ‘play’. If you already have that through family connection, you essentially already have a head-start.

- ‘I want to become an upper-middle class in the US, and considering the options, academia is the one where I’m most likely to succeed, and I’m happy to play the game’: Like it or not, for a first-gen immigrant with good grades to remain in the US, and join the ‘upper middle class club’, academia is still one of the best options. Other such ‘paths’ include: get a CS or related degree and become a programmer and get a job in FAANG, get H1B/green card sponsorship. Or do finance (investment banking, etc.) after undergrad and get similar work visa sponsorship. But there are always people who fail the H1B lottery and has to go back. So if you absolutely want to stay in the US, and set your kids for a good start, academia is really not a bad choice, especially if you’re already good at math and don’t hate research and don’t mind ‘playing’ the game

Wait, but what about ‘I like doing research’?

That’s the elephant in the room right? I’m divided — I came to the PhD because I fell into this category. But what I found is that, for a lot of people who ‘thought’ they like doing research, they don’t really know what research actually means until they’re in grad school. Like it or not, even the full-time RAship doesn’t give you a great idea what a career in research is actually like — the politics, getting ridiculous referee reports where the referee didn’t read the paper, not getting into conferences/journals because you’re not in the club, lots of administrative and teaching responsibility (unless that’s what you like), spending years to write a paper which eventually got 2 cites in a year, feeling that whatever you do is completely irrelevant to the real world, etc.etc.etc. A lot of these you only really feel after you come to grad school, and it’s very hard for you to understand what it’s like no matter how much I talk.

Making your hobby your job is a bad idea. Of course you keep hearing pep talks where people say ‘I made my hobby my job and I can’t be happier’ but the fact that people use that as a pep talk topic means it’s usually hard, and you should realize you’re most likely most people. When you’re doing music for fun, you do whatever you feel like doing; you only do it when you want to; you don’t need to care about what other people think. When you make music your job, by definition it means what you do have to generate money, which means someone need to pay you, which means you need to do things that please other people, which means you have to care about what other people think, and most likely do things you don’t like but please other people, and you can’t just do it when you want to but you have to do it whenever someone wants you to. Replace ‘music’ with ‘research’ and read the paragraph again.

And the interesting thing is, despite the fact that all fields are fundamentally the same, research seem to pretend that it’s a field where ‘people work on things they like’ and ‘things that change the world’. For example, in the world of start-ups, the golden rule is to ‘make something someone needs’ and ‘make something that someone would pay for’ (e.g. read essays from Paul Graham, the Raj Chetty of start-up world) — people are very open and transparent and honest about how things actually work.

So it sounds like I’m against it, why did I say ‘I’m divided on this one’?

From a purely practical perspective: with a econ PhD, you’ll never be unemployed in the US — there are always firms hiring economists/data scientists, and the supply-demand imbalance is even more severe than in CS. You also skip one level if you enter a firm with a PhD, so all in all you don’t lose that much time, and will end up with a very high starting salary.

More importantly, if you really like research, even if you don’t end up in academia, the 4–6 years of PhD can still be fun: I had fun thinking about questions I like thinking about, learnt about the process of writing a paper, wrote some, did some presentations here and there selling my research, got to know some interesting research/papers. I still quite enjoyed the 4 years of my life in the PhD, and I don’t regret doing it. In fact, the reason why I decided to do the PhD was precisely that, I asked myself, if I don’t do the PhD, will I regret it on my deathbed, and the answer is yes.